Learning how a kitesurf kite works can improve your kiting abilities. Understand how your kitesurf kite works and what it needs and you could find yourself reading the environment around you, making for the best sessions of your life. Often a good kiter is a knowledgable kiter!

Table of Contents

How your bar controls your kitesurf kite.

Most modern Leading Edge Inflatable (LEI) kitesurf kites use a four-line bar with two front lines and two steering lines which connect to your kite’s bridles.

The two front lines of your bar connect to the leading edge attachment points and support the force of the kite, but do not control direction. The steering lines connect to the steering bridle attachment points and affect both direction of the kite and the kite’s angle of attack to the wind.

Your kite may have multiple connection options to adjust it’s performance. Take a look at this guide to tuning your LEI kite (link) to understand how you can use these settings.

As you connect your bars chicken loop to your harness, the force of the kite is not felt in your arms but in your core. You are able to control the angle of the kite to the wind by sheeting the bar in or out along the depower throw.

Forces acting on the kite

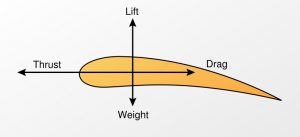

The forces occurring as air passes over and under the kite effect how it flies. Like the wing of an aeroplane, our kite also deals with lift, drag, thrust, and gravity – it also has line tension as an additional force. We’ll quickly introduce these terms before explaining what the effects they have. To keep a kite flying steady the four forces must be in balance.

Lift is the upward force that pushes a kite into the air. Lift is generated by differences in air pressure, which is created by airflow passing above and below the body of the kite. Kites are designed so that air particles moving over the top of the wing, flow faster than the air moving over the bottom. Gravity acts as a downward force on the kite, relative to the weight of the kite. The force of the weight pulls the kite toward the ground.

Thrust is the forward force that propels a kite in the direction of motion. A kite relies on the tension from the lines and moving air created by the wind to generate thrust. Thrust is the reason why the kite will always fly towards the edge of the wind window and won’t stay in the power zone; the kite must fly towards the most upwind point of the wind window.

Drag is the backward force that acts opposite to the direction of motion. Drag is caused by the difference in air pressure between the front and back of the kite and the friction of the air moving over the surface of the kite.

Changing the angle of attack with the bar?

Angle of attack

As the wind reaches the kite, airflow splits at the leading edge of the kite passing over and under it’s surfaces, moving towards the trailing edge, and continuing downwind.

The flow of air going over and beneath the kite reach the trailing edge at the same time. Due to the angle of the kite, the airflow going over the top of the kite must accelerate to reach the trailing edge at the same moment as the airflow passing beneath.

It is this acceleration of airflow over the top of the kite that forms low pressure above the kite and creates lift. The more lift generated, the more it pulls you.

If flying a fixed bridle trainer kite, like the one you use in session one, it’s angle to the wind can only be changed by steering the kite into each zone in the wind window (link). As the kite is flown into the power zone, and the angle of attack is increased, you get the most pull (lift). This is because air is accelerating faster here to reach the trailing edge at the same time as the airflow passing the underside of the kite. You’ll also notice that the kite flies faster through the power zone due to increased thrust.

Sheeting in and sheeting out

If we are flying a depowerable kite, such as the Leading Edge Inflatable (LEI) kite used on the water part of your lessons, the bar can be “sheeted in” and “sheeted out”, pulling the bar closer to us or pushing further away from us along the depower throw. This movement of sheeting on the bar changes the kites angle of attack, giving you additional control over how much lift the kite generates.

Pushing the bar out: (Sheeting out) reduces rear line tension and reduces the kite’s angle of attack so the kite generates less lift. Which in turn pulls the wing tips and the trailing edge of the kite closer to the wind. The result is a tighter turn radius when steering and normally more power, though it is possible to negatively affect the kite by pulling in the bar too much.

Pulling the bar in: (Sheeting in) increases rear line tension and the angle of attack which generates more lift as airflow accelerates over the top of the kite. In this position, the kite generates less power but also has less line tension for controlling direction while steering. With the bar out, the turn radius of the kite will be large and the kite slower to respond to counter steering.

It’s important to remember that this is an additional factor to the amount of lift created by the position of the kite in the wind window. If you steer the kite through the power zone, the kite will still pull you hard, even with the bar sheeted out.

It is possible to “over-sheet” and pull the bar in too far, increasing the angle of attack beyond the kites stable flying range causing unbalanced forces on the kite. When we pull the bar in too far, the airflow over the top of the kite becomes turbulent and can no longer accelerate to the trailing edge to create lift and thrust. This results in an imbalance of pressure above the kite and increased drag. The kite will then “backstall” and fall backwards, instead of flying forwards.

You will be able to recognise when your kite is backstalling as it will feel sluggish, lose power and then fall backwards through its trailing edge. Pushing the bar out will correct this by reducing drag and allowing the kite to fly forwards again.

Our ability to recognise signs of backstalling will enable us to correct our input at the bar and put the kite into a more efficient flying position quickly. A great way to learn this skill is to practice light wind kite flying (link) as you will learn to be more aware of bar position while flying the kite.

Want to know more about the histroy of kitesurf kites? Have a look at this short film about the history of kitesurfing here

NEXT UP: How to launch and land a kitesurf kite